FROM THE CREATORS

Chekhov wrote, “When a person is born, he can

embark on only one of three roads in life: if you

go to the right, the wolves will eat you; if you

go left, you’ll eat the wolves; if you go straight,

you’ll eat yourself.” This is a perfect description

of the life of Dmitri Shostakovich, as well as the

character Kovrin in Chekhov’s story “The Black

Monk.”

I didn’t know this Chekhov story until my

friend Gerard McBurney mentioned it years

ago during our work together with his brother,

Simon, on another music theater collaboration

about Shostakovich,

The Noise of Time.

Gerard

told me that Shostakovich loved the story and

had long planned to write an opera based on

it—a project that never came to fruition. I filed

this information in the “that might be interest-

ing to explore someday” part of my brain.

I have admired James Glossman’s work as a di-

rector, writer, and actor for many years. In the

course of our friendship, we’ve often talked

about wanting to collaborate on something. Two

years ago, I told him about “Shostakovich and

The Black Monk,” and he loved the idea of try-

ing to create something together. Jim gives me

much more credit than my role in this project

warrants. I may have planted the seed, but he

took that idea and wrote a brilliant script, mas-

terfully interweaving Shostakovich’s life with the

Chekhov story.

When I first read “The Black Monk,” I was

struck by the fact that Chekhov refers to some-

one singing Braga’s “Angel’s Serenade” at a party.

I also read that Shostakovich referred in a letter

to “that Italian thing” in the slow movement of

his String Quartet No. 14; this material returns

near the end of the whole quartet. I discovered

that he had made an arrangement of the piece by

Braga, which he clearly intended to incorporate

into his opera. And then I thought of the swirl-

ing passages of fast notes in the String Quartet

No. 15 and realized: This music could represent

“The Black Monk.” That was a key moment in

the process of linking the composer’s music to

Chekhov’s story.

In

The Noise of Time

, we performed the Quartet

No. 15. “Shostakovich and The Black Monk” fea-

tures the Quartet No. 14. We will play the whole

quartet over the course of the evening, but not

in one stretch; the complete story of “The Black

Monk” will also unfold, interspersed with other

dramatic and musical elements. The first move-

ment functions as an overture; the slow sec-

ond movement as an accompaniment to Irina

Shostakovich’s monologue, breaking off at the

end of her spoken “aria.” The slow movement re-

sumes later, near the end of the Chekhov story.

The actors listen to the third movement for sev-

eral minutes before the final dramatic action co-

incides with the nostalgic concluding measures

of the quartet.

We perform the “Angel’s Serenade” in our own

version for soprano and string quartet. Other

excerpts from the Shostakovich string quartets

are drawn upon to complement both stories—

Shostakovich’s and Chekhov’s. I tried carefully

to weave those passages into the complex tap-

estry that Jim had created. Sometimes the music

functions symbolically. For example, the three

percussive chords from the String Quartet No. 8

recur often in the early stages of the drama.

According to cellist/conductor Mstislav Ros-

tropovich and others, if a person who couldn’t

be trusted entered a café or restaurant, someone

would knock three times under the table—“Be

careful what you say!” Elsewhere the music un-

derscores the action, as it does in opera and film.

To the great composer, Dmitri Shostakovich: I

hope we have managed, in our own modest and

respectful way, to pay homage to the opera you

dreamed of writing.

– © 2018 Philip Setzer, Co-Creator and

violinist of the Emerson String Quartet

When Philip Setzer first approached me about

collaborating on a music theater piece for actors

and the Emerson Quartet about Dmitri Shosta-

kovich’s decades-long quest to create an opera

from Anton Chekhov’s classic story “The Black

Monk,” I was, of course, immediately intrigued.

I am deeply moved by Shostakovich’s quartets,

and although I love and have as often as pos-

sible worked with Chekhov’s plays—both the

full-length masterpieces as well as the brilliant,

sometimes underappreciated one-act come-

dies—it had been decades since I had read many

of the stories. What I remembered of “The Black

Monk” was a very 19th-century tale of a seduc-

tively gothic atmosphere luring a promising ac-

ademic into delusion and madness.

What I found upon my return to this text was

a sharp and deeply moving parable about free-

dom and conformity, love and fear, and the

ruthlessly high cost of getting along by going

along—making art and living life, and how haz-

ardous the contradictions can grow. It is a narra-

tive both deeply and profoundly unsettling, and

at the same time thrillingly, even joyously the-

atrical in its exuberant embrace of the “highs”

of creation and the “lows” of terror and of the

unknown. For someone who has been adapting

and directing prose fiction for the stage for over

30 years, this piece seemed to practically leap off

the page.

At the same time, as I began to enhance my gen-

eral knowledge of Shostakovich’s life and career

by beginning to more thoroughly investigate his

personal narrative, decade by decade, from his

growing fame in the late ’20s and early ’30s until

his death in 1975, I became struck by just how

closely the themes of Chekhov’s story seemed to

both parallel and converse with the events and

arc of the composer’s often direly threatened

creative—and physical—life.

First the tremendous reception, both at home

and abroad, to Shostakovich’s opera

Lady Mac-

beth of the Mtsensk District

, helping to raise him

to a suddenly new level of celebrity, of sky’s-the-

limit artistic freedom—followed by the sudden

and unexpected thunderbolt of the front-page

editorial in

Pravda

.

Rumored to have been written by Stalin him-

self—headed “Muddle, Not Music,” which con-

demned his work as “bourgeois formalism”—it

was the sort of public words that often tended

to cause artists in the Soviet Union to disappear,

sometimes forever.

The opera was withdrawn everywhere. Shosta-

kovich’s commissions vanished, and he report-

edly slept for some nights on his landing, in a

coat, with a packed suitcase, waiting to be taken

away to the Lubyanka prison by Stalin’s secret

police, just as friends of his had been so taken.

And yet, somehow, he survived.

And kept composing.

He always kept in favor just enough with

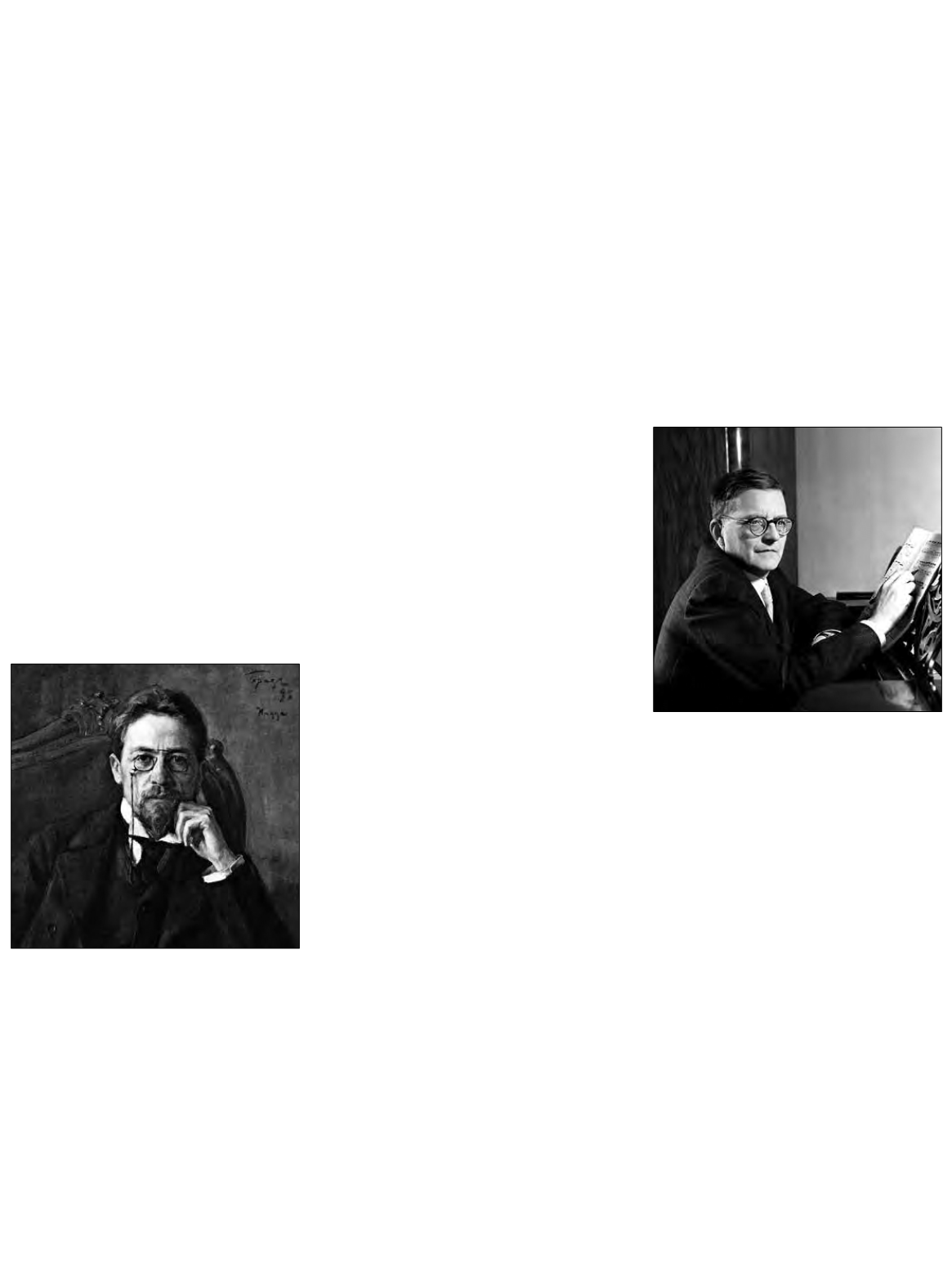

Dmitri Shostakovich (1958)

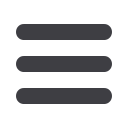

Anton Chekhov by Osip Braz (1898)