LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827)

Overture to

Egmont

, op. 84

Scored for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two

clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets,

timpani, and strings

The great German poet and playwright Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) began his

tragic account of the Dutch military hero Count

Egmont in 1775 during the weeks when he was

waiting to enter the service of Duke Charles Au-

gustus of Weimar. The first draft was completed

at that time and then set aside. Goethe revised

Egmont

several times over the next 12 years, at

one time nearly scrapping the project altogether.

Nevertheless, this tragedy in five acts was com-

pleted during his stay in Italy in 1787. The lyrical

poetic style in

Egmont

reflected the Classicism

of the poet’s later period, although work on the

play had begun while he was occupied with the

dramatic expression of

Sturm und Drang

(liter-

ally, storm and stress). The literary movement

known as Sturm und Drang, especially influen-

tial during the 1770s, took its name from a play

by Maximilian Klinger, written in 1776 on the

subject of the American Revolution. Goethe’s

Egmont

is imbued with many of the same dem-

ocratic ideals of the revolution, in particular, in-

dividual freedom of expression.

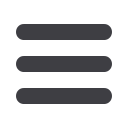

Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavre

(1522–68), was a historically important figure

during The Netherlands’ struggle for indepen-

dence from Spanish rule at the end of the 16th

century. Egmont became governor of Flanders

and Artois after leading his troops to victory at

Saint Quentin (1557) and Gravelingen (1558).

Along with William of Orange and Count Horn,

Egmont signed a letter in 1563 protesting the ty-

rannical actions of Cardinal Granvelle, the king

of Spain’s minister to the Low Countries. The

arrival of the Spanish Inquisition into the Low

Countries three years later caused further dissent.

In 1567, Ferdinand Alvarez of Toledo, the Duke

of Alba, entered Brussels with 20,000 additional

troops. Egmont and Horn were lured to the pal-

ace of the duke, where they were seized, charged

with treason, and beheaded the following year.

In Goethe’s play, Egmont has fallen in love with

Klärchen, who poisons herself on the eve of his

execution. Egmont has a vision of the future in a

dream. The goddess Liberty, having the features

of Klärchen, holds the victor’s laurel crown over

Egmont’s head. The sound of military fifes and

drums awakens Egmont. The guards take him

to meet his executioner. As he leaves, a victory

symphony is played. Egmont’s dream of a nation

independent of Spanish rule was realized only in

1648, at the end of the Thirty Years’ War, when

the Treaty of Westphalia recognized the autono-

my of The Netherlands.

Beethoven had long admired the writings of

Goethe by the time he composed his incidental

music to

Egmont

in 1809–10: an overture, four

entr’actes, two songs (to texts by Goethe), music

to accompany Klärchen’s death, a melodrama,

and the final

Victory Symphony

(

Siegessympho-

nie

). Beethoven created this music soon after the

French troops bombarded, and eventually occu-

pied, Vienna. Egmont’s struggle for democratic

ideals became symbolic of the Viennese spirit

during the French occupation. Beethoven’s inci-

dental music was first performed during a reviv-

al of Goethe’s play at the Burgtheater in Vienna

on May 24, 1810. The overture, not yet complet-

ed, was first heard at the fourth performance, on

June 15.

Beethoven captured the essence of the conflict

in Goethe’s tragedy in the Overture to

Egmont

.

The slow introduction contains two opposing

musical ideas: the first, following the initial

chord, is played by the full strings, and the sec-

ond is a quiet, imitative statement by the winds.

As the tempo increases, the cellos establish a

tragic atmosphere immediately reinforced by

the other instruments. Later, a major-key theme

recalls the dramatic conflict of the introduction

and its two motives played by the strings and

winds. The coda, which adds the piccolo, bor-

rows music from the

Victory Symphony

. The

overture ends on a heroic and triumphal note.

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, op. 15

Scored for one flute, two oboes, two clarinets, two

bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, strings,

and solo piano

Solo improvisations and self-composed con-

certos were the bread and butter of Classical

and Romantic virtuosos. Impromptu creations

required mild caretaking, since rival perform-

ers occasionally stole flashy, novel effects and

passed them off as their own. On the other hand,

virtuosos jealously safeguarded their own con-

certos. Allowing a manuscript copy to circulate

or ushering a work into print essentially termi-

nated the “unique” place the concerto occupied

in the composer-performer’s active repertoire,

requiring a virtuoso to create replacement

works.

As a business-savvy rising keyboard star, Bee-

thoven understood this reality of the virtuoso

profession. He composed two piano concertos

during his first years in Vienna and restricted

these works to his own performances. Beetho-

ven clearly struggled with his first mature piano

concerto. Initial sketches for a work in B-flat

major date from 1793, soon after his arrival in

Vienna. This score underwent two extensive

revisions in 1794–95 and 1798, one before the

premiere on March 29, 1795, and the other af-

ter several performances in Vienna, Prague, and

Berlin.

Beethoven began another piano concerto in

1795, this one in C major. With confidence

gained from the initial concerto exercise, com-

position proceeded without major interruption,

and the premiere took place on December 18.

The composer revised his score in 1800. When

the first two concertos were published in 1801,

Beethoven reversed their order: the C major be-

came No. 1, and the B-flat major No. 2. Six years

had elapsed between the premieres of Beetho-

ven’s two concertos and their publication. By

that time, work on the Piano Concerto No. 3 in C

minor was well under way. Beethoven dedicated

the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, op. 15, to

Countess Anna Luise Barbara d’Erba-Odescal-

chi (

née

von Keglevics), a piano student of his

and an honoree of several early works.

Correspondence with the publisher Breitkopf

& Härtel (April 22, 1801) revealed the nervous

composer attempting spin control with the

press. “In this connection I merely point out

that Hoffmeister is publishing one of my first

concertos [No. 2 in B-flat major, op. 19], which,

of course, is not one of my best compositions.

Mollo is also publishing a concerto that was

written later [No. 1 in C major, op. 15], it is true,

but which also is not one of my best composi-

tions of that type. Let this serve merely as a hint

to your

Musikalische Zeitung

about reviewing

these works. … Advise your reviewers to be

Count Egmont Before his Death

by Louis Gallait

(1848)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1801)