AD

If anyone had a knack

for defying convention with an

astounding rate of success, it was Leonard Bernstein. When

he became music director of the New York Philharmonic in

1958—15 years after his surprise debut with the same ensemble,

then only months into his tenure as its assistant conductor—

the tradition had been for those assistants to remain in the

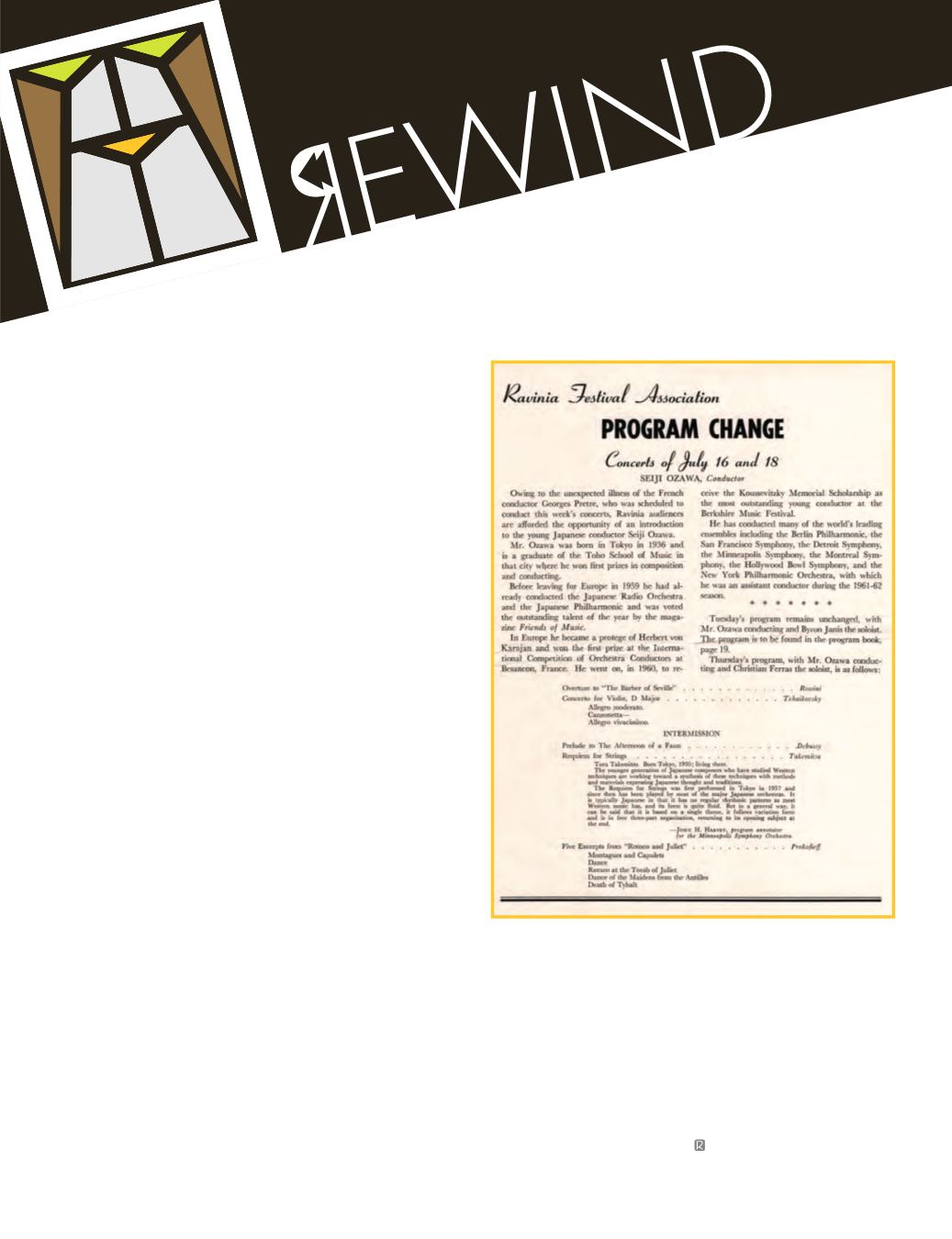

position for only one year. But then Seiji Ozawa caught his

eye. The winner of the 1960 Koussevitsky Prize at Tanglewood,

where Bernstein had been a close advisor for the conducting

and orchestral programs since 1951, and subsequently the win-

ner of a scholarship to study with the quintessential maestro

Herbert von Karajan, Ozawa was quickly sought by Bernstein

to become one of the NY Phil assistants in 1961. One of three

conductors in the role, Ozawa was nonetheless a clear favorite,

being chosen to lead a performance during the orchestra’s 1961

tour and retaining a close association with Bernstein, if unoffi-

cially, through the maestro’s 1965 sabbatical.

The especial attention from “America’s music teacher” of

course drew the attention of other ensembles. Ozawa made

debuts with the orchestras of San Francisco, Minneapolis,

Detroit, and Montreal between 1962 and 1963. During the latter

summer, he received a call similar to that which Bernstein

received in 1943: the conductor for the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra’s concerts at Ravinia has suddenly taken ill at the

11th hour, and could Ozawa come conduct his concerts. Even

with a program inherited from Georges Prêtre, comprising

Beethoven’s Third

Leonore

Overture, Grieg’s Piano Concerto,

and Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony, Ozawa appointed

himself well in his Ravinia and CSO debuts on July 16, with

the

Chicago Daily News

readily recognizing the influence

of “Leaping Lenny”: “While conducting, he [Ozawa] slides

easily from waltz to rhumba to twist to a modified version of

the Limbo … however, he remains in control of the situation.

Ozawa can make an orchestra do almost anything he wants …

it would be hard to name a conductor of his age more gifted,

and it will be fascinating to see what becomes of him.”

The second night, July 18, was opened up to Ozawa, which

caused the

Daily News

to assert, “It is necessary to revise the

glowing estimation that appeared in this space … because by

evening’s end it was becoming hard to think of many more

gifted conductors of any age. This time, Ozawa faced and

passed the only worthwhile test of a conductor: he brought

a new work [Takemitsu’s

Requiem for Strings

], rehearsed the

orchestra in it thoroughly, and then secured a performance

of polish and poetic imagination. Very little time should

elapse before he shows up again at the head of the Chicago

Symphony.” In very little time indeed—just a few days more

than a month later—Ozawa was named the first music director

of Ravinia, where he would bring the flair and passion for the

music of his time (as well as music written specifically for his

time) that he shared so similarly with his mentor, Bernstein,

through the end of the decade.

July 16 & 18, 1963

55 YEARS AGO

ON THIS DATE

JULY 9 – JULY 22, 2018 | RAVINIA MAGAZINE

23