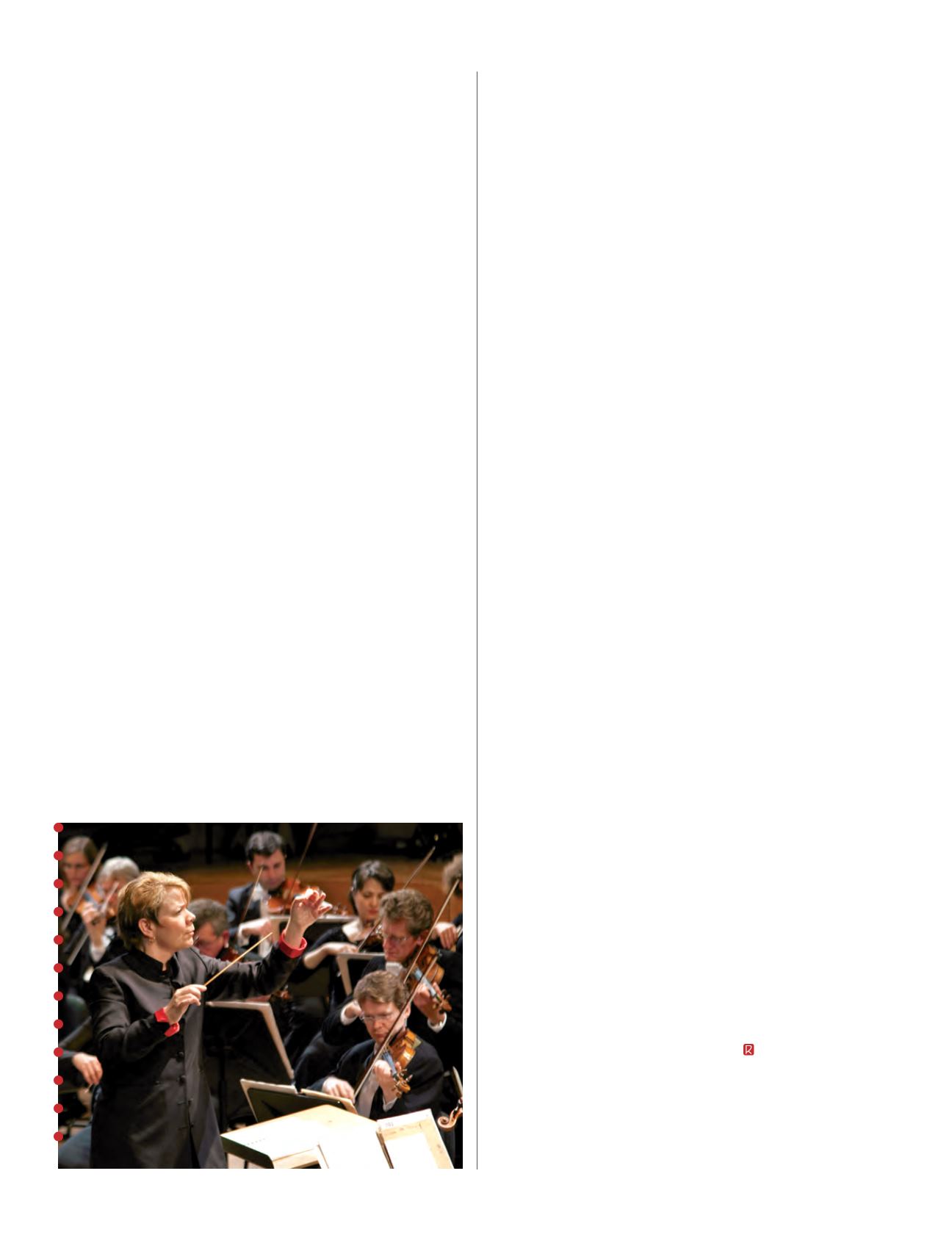

Alsop today, leading a performance by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra,

which she has been music director of since 2007 and is tenured with until 2021.

Concert Series. Titled

Leonard Bernstein: 100 Years Young

, the

morning event features conductor George Stelluto and the

Peoria Symphony Orchestra, soprano Michelle Areyzaga (an

alumna of the Steans Music Institute, Ravinia’s conservatory

for professional musicians), and young student clarinet, violin,

and piano soloists.

“We want people to feel like they’ve gained insight into

this person,” Alsop says, “that they’ve seen the true Leonard

Bernstein and what his huge contributions were on all of these

levels, but also feel entertained. So it’s really trying to balance

things—how much talking as opposed to how much music.

Welz is open to all kinds of crazy ideas, so it’s been fun to work

with him.”

The only disputed side of Bernstein’s legacy has been his

standing a composer. At the time of his death, many critics

were willing to concede his stellar accomplishments in the

realm of musical theater with works like

West Side Story

, but

some of his classical pieces were downplayed or dismissed alto-

gether. But all that has changed in the quarter-century since his

death. Perhaps no creation is more indicative of these changing

perceptions than Bernstein’s

Mass

, a cross-genre theatrical

work commissioned for the 1971 opening of the Kennedy

Center in Washington, DC. It was derided at its debut by

New

York Times

music critic Harold Schonberg as a “pseudo-serious

effort” that was “cheap and vulgar.” But

Mass

is more and more

seen as a masterpiece, a work decades ahead of its time with its

inventive fusion of musical styles.

“When Bernstein was alive,” Alsop says, “it was very

difficult for people to separate Bernstein, the bigger-than-life

persona, from the Bernstein, the composer. Almost impossible.

With time having passed, his music can be listened to and per-

haps assessed without any baggage—just for pure music’s sake.

I think when one can do that, one sees the absolute genius

in this composer. I’ve felt this from the minute I got to know

his music, particularly his ‘serious’ music, that it’s some of the

greatest stuff ever written.”

The first thing Alsop and Kauffman agreed on was present-

ing the rarely heard

Mass

as the centerpiece of this summer’s

Bernstein tribute at Ravinia, and everything else followed

from that. The 1¾-hour work will be showcased July 28, with

Alsop shepherding 275 singers and musicians, including the

100-voice adult choir Vocality. Completing the headcount will

be the CSO, Chicago Children’s Choir, Highland Park High

School Marching Band, and baritone Paulo Szot in the central

role of the Celebrant plus a cast of 22 as the Street Chorus.

Alsop calls Bernstein her “hero.” She first connected with

him in 1987 as a student at the Schleswig-Holstein Musik

Festival in northern Germany, and subsequently was chosen

as a conducting fellow in the summers of 1988 and 1989 at the

Tanglewood Music Center in Lenox, MA. In the months in

between, she studied with him privately, and in 1990, he asked

her to go with him to Japan for the opening of the Pacific Mu-

sic Festival in Sapporo. “So, I was with him until right before

he passed away,” she says.

Among the lessons Alsop carries with her from her time

with Bernstein is his “unbelievable commitment” to the

composer. He saw conductors as “mere messengers” who are

responsible for understanding a musical narrative and com-

municating it to listeners. “His music is all about exploring

this concept of faith, whether its faith in humanity or faith

in spirituality,” she says. “And for him, often in his music, it’s

a simplistic idea, but the way he executes it is anything but

simplistic—this idea of tonality versus atonality, which was

so prevalent and so topical when he was at the height of his

composing career. And it becomes a symbol for a crisis of faith.

Knowing him really enhances that narrative for me.”

But she tries to bring that same responsibility she feels

toward Bernstein’s music to every other composer as well, just

as he would have wanted. “People sometimes thought, he’s too

flamboyant or too this or too that,” she says. “But I understood

that Bernstein was actually channeling the composer he was

conducting always. When he was conducting Mahler’s Ninth

[Symphony], he felt he was Mahler. He was really feeling it.

And that was an incredible inspiration to watch as a young

conductor.”

Although future plans have not been announced, Alsop’s

curatorship is open-ended. Ravinia intends to continue its

Bernstein celebration at least a few more years because of the

wealth of his accomplishments in so many spheres. Alsop

noted that this year’s schedule does not allow her time to work

with the artists at Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute, something

she intends to do in 2019. Future looks at Bernstein might

explore his wider work in musical theater, for example, or tie

into other anniversaries.

“I don’t think it’s going to be as opulent as this summer ev-

ery single year, but it could be,” Kauffman says. “Who knows?

There’s certainly plenty of work to do.”

Kyle MacMillan served as classical music critic for the

Denver Post

from 2000

through 2011. He currently freelances in Chicago, writing for such publications

and websites as the

Chicago Sun-Times

,

Wall Street Journal

,

Opera News

, and

Classical Voice of North America

.

BRUNO VESSIEZ

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JULY 9 – JULY 22, 2018

28