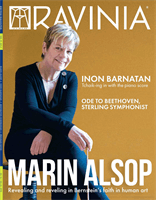

By Marin Alsop

/

/

, on

July 12, is a great introductory

program to Leonard Bernstein

because it runs the emotion-

al gamut. The Overture to

Candide

has to be one of the

most successful overtures

ever written for music theater.

In four minutes he’s able to

capture all of this fantastic

craziness and it makes you feel

just so joyous. And from there

we go explore the depths of the

Serenade (after Plato’s Sym-

posium)

, which sounds really

highbrow, but with Bernstein

telling this story, it’s really just

the story of a fantastic dinner

party. Everyone is sitting

around and they’ve had a few

drinks, and then they decide,

oh, let’s talk about a subject,

let’s talk about love. So each

person in the circle begins to

speak about love, and the deal

is that wherever the speaker

that precedes you leaves off,

you have to pick up, so the sto-

ry evolves. And that’s exactly

what happens in the piece; the

themes are carried through.

Then, for instance, there’s

Aristophanes, who’s had too

much to drink, so he’s hiccup-

ing, and you can hear it in the

music. Eventually it devolves

into this sort of drunken romp

and they end up having a

huge party, and this, to me, is

kind of a perfect microcosm

of Bernstein himself. You can

have this extremely high-level

discourse and end up having

a downright fantastic party

together. And then we go to

Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony,

the “Pathétique”; of course, it

was a flagship piece for Bern-

stein. When he conducted this

piece—when he conducted

anything

—he embodied the

composer. It was always an

intensely emotional journey

because, of course, this is the

last piece Tchaikovsky wrote.

It’s a piece that’s fraught with

conflict. I remember talking

to Bersntein so much about

this compositional technique

called

appoggiatura

, a note that

needs resolution, so there’s this

constant pulling with it—ev-

erything needs resolution, but,

of course, in the end, there is

no resolution.

for Bernstein, in particular

Beethoven’s philosophy, that

he believed in the power of

love and the power of human-

ity, the power that humans

have when they unite with

each other. There Bernstein

was, playing Beethoven’s

Ninth Symphony when the

Berlin Wall came down. There

he was, changing the word

joy

to the word

freedom

, and

that took a lot of audacious

courage. It was so Bernstein,

saying, “I know that Beetho-

ven would be here and he

would’ve done this.” He had

that commitment to stand up

and be present when things

were happening. He said our

response to violence will be

to make music more intense-

ly. That is what he did at so

many spark points in the

world. Beethoven’s Ninth and

Bernstein’s

Chichester Psalms

on the July 14 concert felt like

the perfect partnership. We

have this glorious piece that

Bernstein wrote for Chich-

ester Cathedral, for a very

Christian setting, but all the

text is in Hebrew. Not only

that, but there are all these

jazz elements, and he wants to

connect us to the innocence

of when we were young, so he

calls for a boy soprano in the

beautiful second movement.

I think writing a piece like

this, for this setting, was just

quintessential Bernstein.

Transcribed and

abridged

from video

interviews

with

Marin

Alsop by

Ravinia

ADRIENNE WHITE

RAVINIA MAGAZINE | JULY 9 – JULY 22, 2018

30